With the world facing environmental catastrophe from climate change, and calls for Europe to stop using all fossil fuels, why is the EU continuing to allow investment in gas infrastructure?

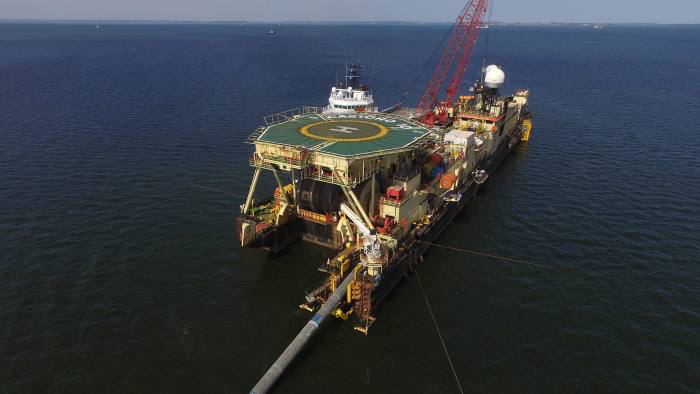

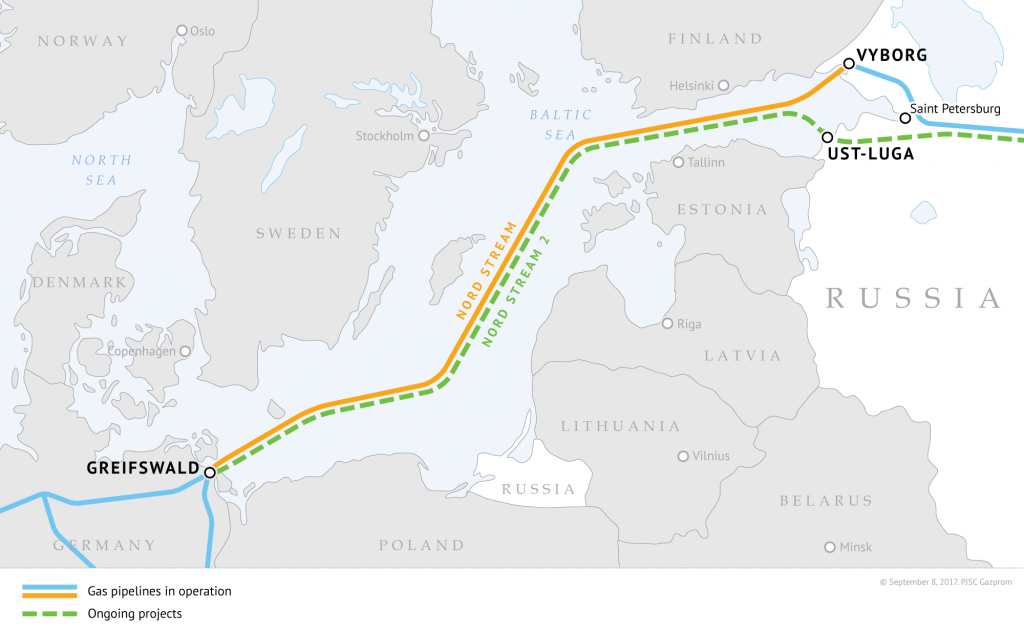

Nord Stream 2 is entering the final stage of its construction after Denmark issued a permit to lay the pipe in its territorial waters. But a new report by the Da Vinci Analytic Group warns that continuing the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline construction before clearing the Baltic Sea seabed of chemical warfare agents threatens to lead to an irreversible environmental impact and will make impossible the use of the sea for fishing or recreation.

The Danish Energy Agency granted Nord Stream 2 AG permission to build part of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline on the country’s continental shelf southeast of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea.

Between 1947 and 1948, the Soviet Union dumped east of Bornholm Island an arsenal of chemical weapons, left after World War 2, containing highly toxic agents, in particular, adamsite, diphenylchloroarsine, and mustard gas. The disposal was carried out through dumping munitions (aircraft bombs and artillery mines and shells) into the sea. It has been established that part of the arsenal was dumped in cases while ships carrying them were still on their way to the designated area. Some of the wooden cases have drifted outside the planned dumping zone.

Munitions cases are still occasionally washed up on the coasts of Bornholm and the southern coast of Sweden, and the exact location of the entire arsenal of chemical weapons disposed of in the Baltic Sea remains unknown. In many instances, fishermen have found these chemical weapons outside the designated dumping site. The precise locations of dumping sites are not accurately charted.

A report drawn up in 1994 by the Special Working Commission on Chemical Weapons Utilisation of the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM CHEMU) in 1994 recommended that any operations to pull up chemical weapons from the seabed were dangerous and should not be attempted.

The 2009 Nord Stream Espoo Report states that the only way to clear the seabed of chemical munitions is to detonate them. But, the detonation of chemical munitions would lead to horrific contamination and an increase of toxic substances in the sea, which would pollute marine organisms. The vast majority of the Baltic Sea bottom is covered with green, black or brown sedimentary gyttja clay making the detection of dumping sites difficult.

Laying the gas pipeline in the Baltic presents a high risk of damage to the integrity of munitions or their accidental detonation through vibration caused by the construction works, which would result in massive ecological damage to the Baltic Sea and possibly cause structural damage to any pipelines.

Chemical warfare agents can retain toxic properties. For example, mustard gas is poorly absorbed by water; it is an enzyme poison that has no antidote, and has a mutagenic effect. When mustard gas is exposed to water, two products are formed, which are more toxic than mustard gas itself. Just one or two molecules of mustard gas penetrating any organism is enough to lead to an emergence in three to four generations of pronounced mental and physical deviations from the norm. In the Baltic Sea, there have been cases of fishermen catching clots of mustard gas weighing 105 kg.

The decomposition of munitions giving off toxic substances in the Baltic Sea can accumulate in marine flora, plankton, and fish. Fish exposed to hazardous substances or products of their decomposition, which are consumed by humans, retain strong toxic and mutagenic properties. The genetic consequences are irreversible.

Bornholm and Gotland Basins are traditional fishing locations. Despite the ban on fishing in certain parts of the Baltic Sea, which has been in effect since the 1960s over the dumping of chemical weapons, further deterioration of the integrity of munitions due to corrosion and possible damage through the construction of the pipeline increases the threat to marine fauna and flora. This poses a serious potential threat to the economy of the Baltic States, Sweden, Germany, Norway, and Denmark. The pattern of underwater currents in the sea indicates that chemical weapons are most likely to drift eastwards, exposing the inhabitants of the Baltic coast to risk.

So the question that Europe faces now is, should we permit continued investment into a gas distribution system with the construction of Nord Stream 2 which has a limited useful shelf life, because the climate emergency we all face means that in any case we must stop using all fossil fuels as quickly as possible? Or should we risk continuing its construction in the knowledge that to do so may damage irretrievably the marine environment of the Baltic Sea for many generations to come. If we are to be serious about tackling the climate crisis that the world is facing, then there can be only one coherent answer possible, namely that the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline must be halted, and the project shelved indefinitely.