By Ian Bond

China’s decision to impose a new security law on Hong Kong has been driven off Europe’s front pages by racial tension and violence in America and elsewhere. Beijing may think that it has got away with curtailing Hong Kong’s autonomy. EU leaders may think that having (feebly) protested, they can focus again on their commercial interests in China. But Beijing’s effort to tighten its grip on Hong Kong is one of several indicators that China is becoming less of a partner and more of a problem for Europe.

What has China done? The Basic Law (Hong Kong’s 1997 ‘constitution’) instructed Hong Kong to “enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition or subversion” against the Chinese government. Faced with popular opposition, however, Hong Kong’s government never did so. On May 28th, China’s ‘parliament’, the National People’s Congress (NPC), authorised its standing committee to draft a security law and include it in the Basic Law – even though the Basic Law itself makes this the responsibility of the Hong Kong government. The text of the new law has yet to appear, but the NPC resolution says that it is intended to “prevent, stop and punish” separatism, subversion or terrorist activities, as well as “activities by foreign and overseas forces that interfere in the affairs” of Hong Kong. The Chinese Communist Party’s interpretation of such offences in China itself is very broad. The NPC also authorised China’s national security agencies to set up institutions in Hong Kong – something that they have not (legally) been able to do so far.

Why act now? China may have judged that the risk of allowing pro-democracy sentiment to grow in Hong Kong outweighed the cost of undermining the principle of ‘one country, two systems’. In 2019, there were widespread pro-democracy street protests in Hong Kong, which alarmed Beijing. And the authorities may have judged that they had an opportunity to act while the rest of the world was distracted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

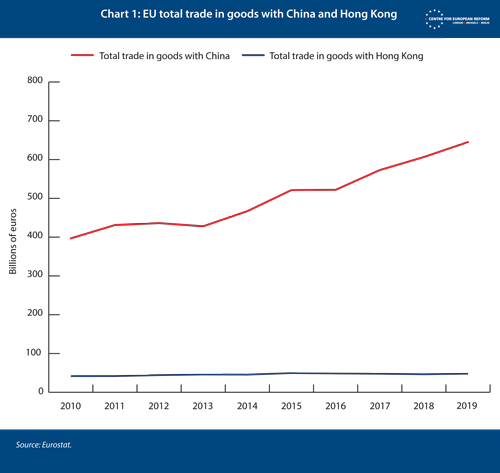

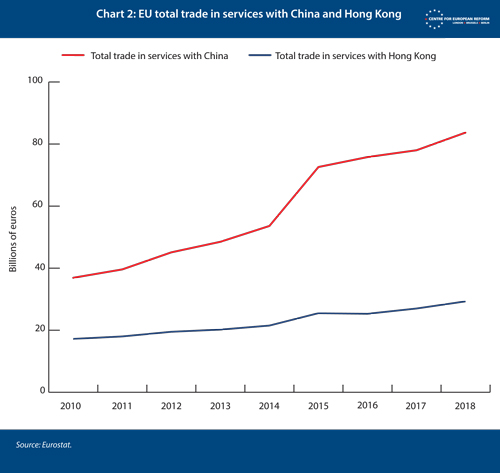

Hong Kong is less vital to China’s economy than it once was. When it passed from British to Chinese control in 1997, Hong Kong accounted for more than 18 per cent of China’s GDP; now it is less than 3 per cent. Its role in trade between the EU and China is also shrinking: in 2010, goods trade between the EU and Hong Kong accounted for 9.5 per cent of trade between the EU and China as a whole, a figure which had fallen to less than 7 per cent by 2019 (Chart 1). Because Hong Kong is a major financial centre, it still plays a disproportionate role in trade in services between the EU and China, though this too is declining: from 32 per cent of trade in services with China as a whole in 2010 to 26 per cent in 2018 (Chart 2).

Still, China’s move is not economically risk-free: Hong Kong remains an essential venue for foreign investors and Chinese companies to do business in a legal and regulatory environment where both feel comfortable. According to the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, a government agency, two-thirds of all foreign direct investment flows to China in 2018 came from (or via) Hong Kong; and investment from Hong Kong made up over half of the stock of FDI in China.

Many European companies use Hong Kong as a base for their operations in China. In 2019, the European Commission estimated that 2,200 EU firms had headquarters in Hong Kong, and about 350,000 EU citizens were resident there (though those figures may have been reduced by Brexit). But the EU’s formal relations with Hong Kong are relatively limited. There is a 1999 agreement on customs co-operation, partly designed to protect European intellectual property rights. There have been discussions on whether to negotiate a bilateral investment agreement and a mutual recognition arrangement for Authorised Economic Operators, but little sign of progress in recent years.

So far, the EU has implied that the new security law will not have much impact on its relations with Hong Kong or China. Speaking to the press after an EU foreign ministers’ video conference on May 29th, Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, said that China was “a competitor, a partner, an ally, a rival”, and the EU had to continue its engagement with China based on its interests. He did not think that sanctions were the way to resolve problems with China, or that events in Hong Kong put at risk investment deals with China.

Both Republicans and Democrats in the US are taking a tougher line. US relations with Hong Kong are governed by the US-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992, which gave Hong Kong some trade and investment advantages. These can be suspended, however, if the US president determines that Hong Kong is not sufficiently autonomous to justify being treated differently from the rest of China.

In November 2019, the US Congress passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, amending the 1992 law. The US secretary of state must now report annually on whether Hong Kong is still autonomous enough to merit the benefits promised in 1992. Congress also instructed the administration to impose asset freezes and visa bans on Chinese officials responsible for any serious human rights violations in Hong Kong – a provision similar to the so-called ‘Magnitsky Act’ of 2012, designed to punish Russian officials responsible for the murder in prison of the lawyer Sergei Magnitsky.

On May 27th, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that the security law fundamentally undermined Hong Kong’s autonomy and freedoms – a step likely to lead to the withdrawal of trade and other benefits. On one level, if the benefits depend on Hong Kong’s autonomy, and Hong Kong is no longer autonomous, then there is no reason to maintain the benefits. But if the US wants to incentivise China to maintain Hong Kong’s distinct character, then it should not withdraw Hong Kong’s privileges until there is clear evidence of how China is using the new law. The US is now at risk of doing more damage to Hong Kong than to the Chinese Communist Party.

The EU, by contrast, must ensure its response is not so low-key that China discounts it entirely. The EU may not be able to change China’s course radically; but that does not mean that it has to shrug its shoulders and write off Hong Kong.

The EU should see China’s willingness to override the Basic Law and the Joint Declaration in context. China is being more aggressive towards countries that criticise its handling of the coronavirus pandemic, such as Australia. It is pushing its territorial claims in the South China Sea and border dispute with India in the Himalayas more assertively. It is taking a more belligerent approach to Taiwan. Its diplomats in Europe, most notably in Sweden, have directed insults at their host countries. There is a pattern of confrontational behaviour here.

In a speech to a conference of German ambassadors on May 25th, Borrell called for a more robust EU strategy for China; but in his May 29th press conference he was vague about its timing and content. Though the special summit meeting between Xi Jinping and the leaders of EU member-states, scheduled for Leipzig in September, has since been postponed, Borrell and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen should still prioritise work on a comprehensive and realistic China strategy, based on last year’s EU-China ‘Strategic Outlook’. In that document the EU for the first time identified China as a “systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance”, as well as a partner and competitor in various fields.

In the interim, the EU needs to get its messages right, both to Beijing and to supporters of democracy in Hong Kong, who need to know that Europe has not forgotten them. Borrell’s declaration on behalf of the EU on May 29th was insubstantial by comparison with the statement issued by the foreign ministers of Australia, Canada, the UK and the US on May 28th. He went further in his meeting with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi on June 9th: he told a subsequent press conference that he had said that China needed to take steps to de-escalate the situation and to respect its international commitments, and referred to the 1985 Sino-British Joint Declaration (which guaranteed Hong Kong’s autonomy until 2047). The joint declaration was registered as an international treaty at the UN by both parties; that means that its provisions, including on Hong Kong’s autonomy and on civil and political rights, cannot simply be a matter of China’s internal affairs.

It would be unrealistic and counter-productive for the EU to threaten economic sanctions against Hong Kong as a way of punishing Beijing, particularly when the new law has not (yet) been abused. But the EU needs to warn Beijing – in private at first, but publicly later, if necessary – that Hong Kong’s attractiveness to investors depends on the rule of law and not the rule of the Party remaining supreme there. In the short term, the Chinese authorities may be able to strong-arm Western investors into making supportive statements about the new law, but in the longer term businesses will draw their own conclusions about the changing business environment and the extent to which their investments will still be protected.

While the EU should not follow the US lead on Hong Kong in all respects, it should start contingency planning for Magnitsky-style measures against any Chinese or Hong Kong officials involved in serious human rights abuses connected with the new laws. The EU has been thinking about the need for a sanctions regime to tackle gross human rights violations since the end of 2018; Borrell said in December 2019 that EU foreign ministers had agreed to launch preparatory work on it. He should accelerate the work. At the same time, like the UK and US, the EU should also be willing to offer refuge to democracy activists from Hong Kong if they face persecution for their beliefs or their advocacy.

The EU should ensure that member-states are applying export controls on China consistently and with regard to human rights issues, including in Hong Kong. The EU has had an arms embargo on China since the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, but different member-states have interpreted it in different ways. China is also a major destination for EU exports of dual-use goods (those with both a civilian and a military application). Work has been going on for some years to update the 2009 EU Dual-Use Regulation, to include human rights considerations and to put tighter controls on surveillance technology, among other things. The Council has resisted the efforts of the Commission and the European Parliament to make the dual-use control regime stricter. In a CER policy brief in 2019, Sophia Besch and Beth Oppenheim argued in favour of tighter regulation and more consistent interpretation of the rules – something which is even more necessary in dealing with a market as large as China.

EU action will be more effective if it is co-ordinated with like-minded countries, especially those in the region, such as Australia and Japan, but also with the UK. Despite Brexit, the UK should welcome EU support for Hong Kong: it would be harder for Beijing to insinuate that EU statements of concern are cover for British or American attempts to encourage Hong Kong to secede from China. The EU should also consider how it can give more political support to democracies in the Asia-Pacific region that are under pressure from Xi’s China – including Taiwan.

Even in concert with other powers, the EU cannot save Hong Kong’s autonomy, if China is determined to snuff it out. But the Union should do what it can to encourage Beijing to hold back, and to ensure that China understands that there could be no rapid return to business as usual in the event of major repression in Hong Kong. If the EU wants to be taken seriously as a geopolitical player, its response to events in China and Hong Kong must be more than hand-wringing.

The Author, Ian Bond, is the Director of Foreign Policy at the Centre for European Reform.