On 14 September, Chinese leader Xi Jinping embarked on a three-day trip (Sept. 14–16) to Central Asia, where he is visiting both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. During his trip, he will attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in the southeastern Uzbekistani city of Samarkand and meet with his Russian counterpart, President Vladimir Putin, write Jianli Yang and Lianchao Han

This is the first time that Xi has stepped out of China in two and a half years since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in Wuhan. Xi seems to be going out of his way to embark on this international trip. After all, in theory, he should be laser-focused on the CCP’s 20th National Congress, during which he expects to be granted an unprecedented third consecutive presidential term, perhaps eventually becoming “emperor” for life. Of course, it’s generally ill-advised for world leaders to leave domestic soil at the helm at such a critical moment.

Therefore, in all likelihood, Xi must have a super-important agenda.

The escalation of U.S.–China tensions in recent years and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have led Xi Jinping to believe that in order to continue to achieve “the great rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation,” China must cultivate allies and gang up against the U.S. and its democratic allies around the world. This is good timing to begin realizing this idea in Eurasia because Beijing will undoubtedly be the “head honcho,” with a much weaker Russia as a junior partner.

It’s also natural for Beijing to further develop the SCO, one of the rare international security alliances that was initiated by China and is headquartered in China. Notably, this year, Iran and Belarus (two staunch enemies of the West) will be joining the summit, alongside the eight other SCO members — China, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, India and Pakistan. With the exception of India, these member-states are likely to support the idea of further developing and strengthening the SCO to become a strong Eurasian counterpart to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Underlying the military and security alliances are close economic ties. Xi certainly wants to bring together the aforesaid allies with his signature “Belt & Road” initiative (BRI), demonstrating China’s ever-growing influence on the world stage. This is the primary reason why Kazakhstan was chosen as Xi’s first stop for his momentous SCO trip.

Kazakhstan is an important partner for China in Central Asia — not only for its mineral, metal and energy resources, but also as an important hub for transportation between Europe and China. It was in Kazakhstan that Xi Jinping announced the “One Belt, One Road” initiative in 2013. Xi delivered a speech at Nazarbayev University (a research university in the Kazakhstani capital of Astana), emphasizing that Kazakhstan is a key node in China’s “Silk Road Economic Belt” (referring to overland transportation routes through landlocked Central Asia), and that China and Kazakhstan enjoy a long-standing, mutually beneficial friendship. Xi proposed that Kazakhstan and China collaborate to jointly build the Silk Road Economic Belt. As the Belt & Road initiative nears its tenth anniversary, Xi is once again starting from Kazakhstan. This is both symbolic and significant.

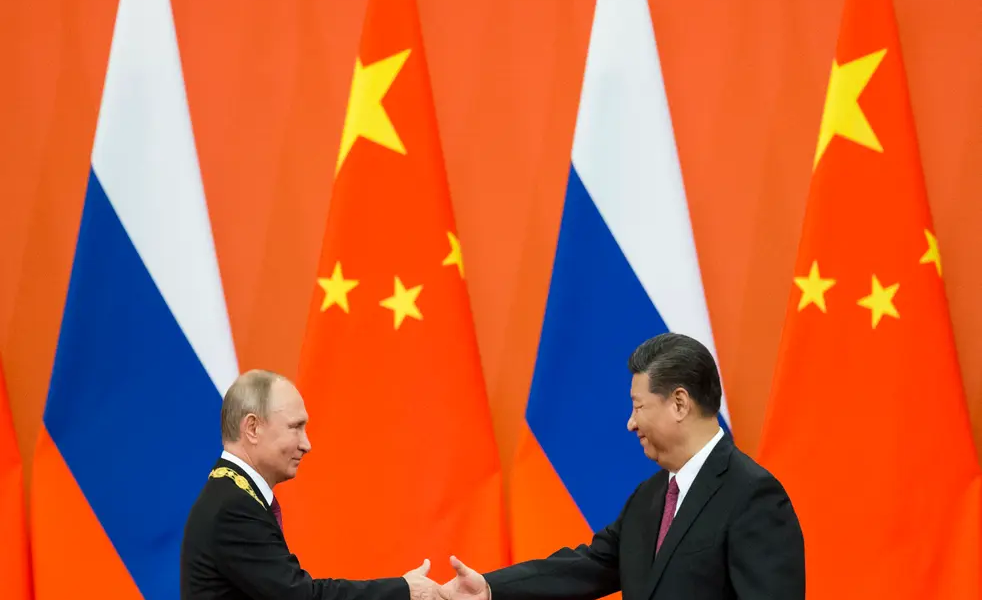

Xi’s meeting with Putin during the SCO summit is a highly strategic move for both leaders. As the authors of this article predicted in an April article entitled “The West Must Not Let Xi Jinping Protect Putin and Give the CCP Another ‘Strategic Opportunity’”, turmoil and tension between China and the U.S.-led democratic world were bound to ensue around the Russo-Ukrainian War, and one of the focal points will be Putin’s political fate. Many democracies around the world have been proactively collaborating to end Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in a way that would spell the end of Putin’s oppressive regime. And, even if Xi deems it vital to China’s geopolitical interests, he would still struggle to bail out Putin. “Xi understands well,” we argued, “that if Putin’s regime falls, China will lose an important bulwark. Because of the fundamental value disparity between China and the democratic world as well as the strategic and economic competition, the CCP will inevitably become a direct protagonist on one side of a new cold war, prematurely bringing China into a full confrontation with the democratic world.”

For Xi Jinping, that timing is coming as Ukraine’s offensive is pushing Russia back; and some members of Russia’s duma (the nation’s legislative assembly) are demanding that Putin step down. Xi will continue to support Putin at the SCO summit and project China’s potential role as a mediator that could be vital in ending the war, even if it entails preserving Putin’s dictatorial regime. In August, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky sought direct talks with Xi to help end Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To date, Xi has yet to respond. After meeting with Putin, Xi will seize the opportunity to hold talks with Zelensky, during which he will position himself as a prospective mediator between Russia and Ukraine. After all, Xi and the CCP recognize that Ukraine has continuously sought close ties with Beijing in the years preceding the conflict and has adopted significant BRI projects in the country. As the ashes of war settle, Ukraine will undoubtably need China for post-war reconstruction. (According to some estimates, it may cost Ukraine upwards of $350 billion to rebuild the country following Russia’s invasion.)

A post-war Russia ruled by Putin — a much weaker nuclear country — would be unable to challenge China’s geostrategic interests for several years (or even generations) to come, but it would nonetheless cause problems for the U.S. and other world democracies, and distract them from effectively responding to China’s expansionist aspirations. Think of the diplomatic benefits that a nuclear North Korea has brought to China over the past decades.

Assuming the stars align for Xi, then the continuance of Putin’s totalitarian regime, the expansion the Beijing-dominated Shanghai Cooperation Organization to counter NATO and other Western coalitions, and the ever-growing Belt & Road initiative will afford China another “period of strategic opportunity.”

The Authors:-

Dr. Jianli Yang, is a former political prisoner of China and a Tiananmen Massacre survivor. He is founder and president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China and the author of For Us, The Living: A Journey to Shine the Light on Truth.

Dr. Lianchao Han is vice president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China. After the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, he was one of the founders of the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars. He worked in the US Senate for 12 years as a legislative counsel and policy director for three senators.