Despite the gravity of the war in Ukraine, the focus of the new US National Security Strategy is China. The document says plenty about the importance of technology, but ignores the relevance of trade to national security, writes Carl Bildt.

The National Security Strategy (NSS) issued by each US administration is always a key document. It is of particular interest to note how priorities and policies evolve between the different administrations in Washington.

In March 2021 I published a paper for the European Council on Foreign Relations that compared the Interim National Security Strategy that the then incoming Biden administration had just published with the previous ones of the Obama administration in February 2015 and the Trump administration in December 2017.

There were obvious differences, such as the shift from ‘America Alone’ to ‘America and Allies’ between 2017 and 2021. There were also more subtle shifts running through all three documents, notably from the 2015 endorsement of an ambitious free trade agenda to Trump and Biden’s retreat from any coherent trade policy. The gradual rise of China was a feature of all the documents.

On the interim strategy in 2021 I concluded: “the US will now prioritise strategic competition with China, a new approach to trade, the rise of technology, the defence of democracy, the urgent climate and health crises, and efforts to avoid ‘forever wars’ in the Middle East”.

It took until October 2022 to issue the final National Security Strategy, reflecting the fact that the global situation has turned out to be more challenging than the authors of the interim strategy had foreseen. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 fundamentally altered the strategic situation, while it took longer than anticipated to hammer out a coherent approach to China.

It also proved hard to fit the different policies into the framework of competition between democracy and authoritarianism that was prominent in the early days of the Biden administration. The December 2021 Summit of Democracies, though much discussed in advance, was a fairly low-key affair, and follow-up efforts have been lacklustre.

The essence of the global situation is a sharp rise in geopolitical rivalry, undermining efforts to seek global co-operation, and an equally sharp rise in the number of global challenges that require a global response. Both the geopolitical rivalry and the common challenges are likely to grow in gravity, and finding a balance in handling them will be crucial in the decades ahead.

The most obvious difference between the 2021 interim strategy and the final NSS is the description of Russia. The interim strategy talked about a “strategic challenges from an assertive China and destabilizing Russia”. While Russia was described as a “disruptive” actor on the global stage – as in 2017 – there was nothing indicating that it should be seen as a threat to the regional order in Europe.

The thrust of the initial policies of the Biden administration was accordingly to seek a stable and predictable relationship with Russia, so as to be able to focus more on the growing challenge of China. The US and Russia announced a dialogue on strategic stability as a possible prelude to a new strategic nuclear arms control arrangement.

The new NSS, by contrast, says that “Russia now poses an immediate and persistent threat to international peace and stability”, and that “over the past decade, the Russian government has chosen to pursue an imperialist foreign policy with the goal of overturning key elements of the international order”. This change was not reflected in the past decade’s security strategies.

The NSS is not designed to go into day-to-day issues, but the Russian war against Ukraine unavoidably figures. The document states that “alongside our allies and partners, America is helping to make Russia’s war on Ukraine a strategic failure”, but is vague on what that means, saying only that “some aspects of our approach will depend on the trajectory of the war in Ukraine”. In outlining the aims to be achieved it expresses support for the freedom of Ukraine, for its economic recovery and its integration with the EU – but does not mention the country’s territorial integrity, unlike recent G7 and other international statements.

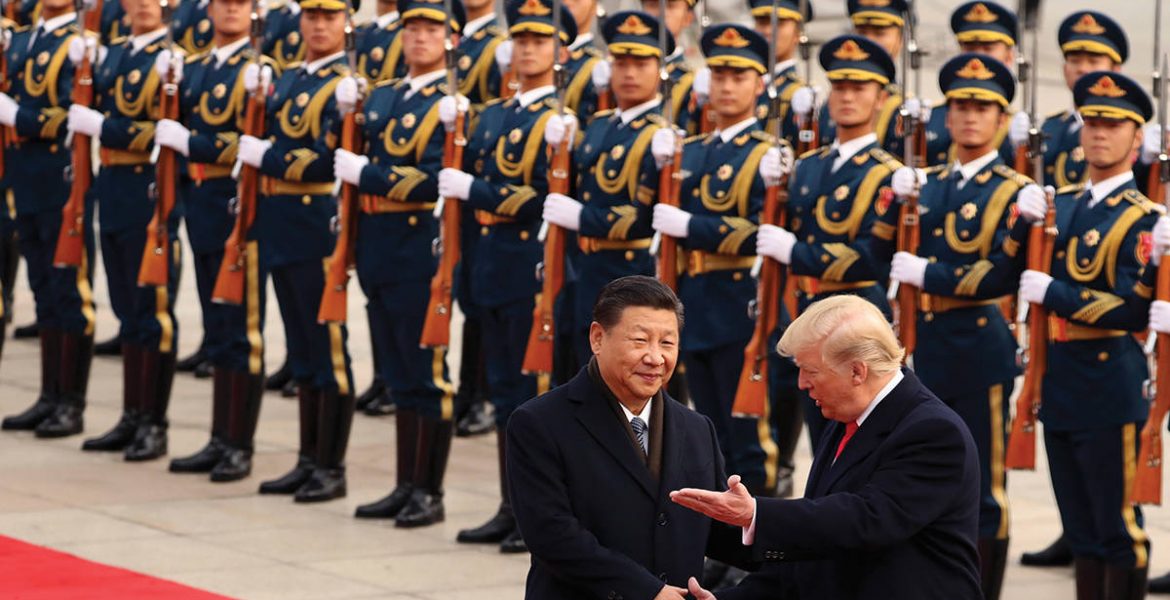

While Russia is described as both an imminent and a persistent threat, the challenge of China is seen less in terms of any imminent threat but more in the light of the long-term implications of the shifting power relationship between the US and China.

Accordingly, the NSS says that China “is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do so”. It is, to paraphrase Thucydides, the rise of the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power of China, and the fears this installs in the United States, that makes confrontation highly likely.

According to the NSS, China has “ambitions to create an enhanced sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific and to become the world’s leading power”. The NSS further stresses the importance of this aim by asserting that the Indo-Pacific region will be the epicentre of 21st century geopolitics. It thus relegates everything in the European area or elsewhere to a lower level of concern.

The strategy towards China, as previously outlined by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in a speech on May 26th, has three components: first, investing in the competitiveness of the US itself; then aligning these efforts with a network of allies and partners; and finally “competing responsibly” in different areas.

But even as this “responsible competition” goes on there should also be a search for a common ground on concerns including “climate, pandemic threats, non-proliferation, countering illicit and illegal narcotics, the global food crisis, and macroeconomic issues”. Responsible competition with China concerns primarily the fields of economy and trade. Yet the NSS focuses largely on technological competition, while almost ignoring trade policy.

There is indeed a fierce competition for control of the technologies that will shape the future, but the competition to develop trade links and economic integration is equally important in shaping political relationships with different parts of the world. Today few countries still trade more with the US than with China. Trade and economic links have become the most important of China’s instruments for growing its presence and position around the globe.

But the NSS shows that trade remains the blind spot of US strategic thinking. In its 48 pages there is just one sentence stating that “America’s prosperity also relies on fair and open trade”, with the word “free” noticeably absent, and another sentence recognising that “globalization has delivered immense benefits for the United States and the world”. When it comes to policy conclusions, however, the NSS is distinctly thin.

There is repeated mention of the so-called IPEF but this is a loose arrangement not really covering trade and market access, hardly taken seriously even by the 13 countries that have signed it. There is no mention of how trade and economic agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or even the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), with China seeking to join the former and a member of the latter, are gradually creating tighter economic integration in the Indo-Pacific region and consequently reinforcing relations between these nations.

The NSS does not even mention the World Trade Organisation, and previous ambitions to seek to reform it have evidently been jettisoned. Instead there is talk of efforts “beyond trade” to deal with different aspects of international economic relationships, though whether that should be done through common international bodies or not is left open. So on the important global trade issue, the NSS confirms that the US has resigned from any ambition of global leadership. Brussels has already taken note, and certainly Beijing as well.

The NSS has a different attitude to technology, describing it as “central to today’s geopolitical competition and to the future of our national security, economy and democracy”. While previous national security documents – notably in 2015 and 2017 – had a tone of confidence about the US position, now it is very different. The NSS calls for massive investments, and there is talk of a “modern industrial strategy” as well as “anchor[ing] an allied techno-industrial base” to safeguard shared prosperity and security. Particular mention is made of “microelectronics, advanced computing and quantum technologies, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and bio manufacturing, advanced telecommunications, and clean energy technologies”.

Part of this programme is reflected in the massive $52.7 billion provided by the recently passed Chips and Science Act, for the R&D and manufacturing of chips, adopted in August 2022. At about the same time that the NSS appeared, the Biden administration announced a ban on the export of high-end semi-conductors to China; this ban extends to any such chips made with US equipment.

Industrial policies are not always successful. Substantially upgraded financing of basic science and research is certainly sound policy, and here the new thrust of US policy is undoubtedly correct, but the next stage is often more complicated. Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Elon Musk were not products of industrial policies but of individual talent and raw entrepreneurial drive.

The main driver behind these policies is fear of what Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2035’ programme, with its massive public funding, can achieve. But whether that program really gives value for money is not entirely clear. Whether the right answer is to set up a mirror ‘Made in US 2035’ is debatable at best.

The EU should take note of two important aspects of the US approach. The first is the declared intention of US policy to attract the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) talent of the world to its universities, laboratories and firms by the sheer scale of the funding available. If EU countries do not substantially increase their corresponding funding there will be a brain drain that will further erode the basis for the future competitiveness of European economies.

The second is the protectionist temptation in these programmes, which risks seriously undermining the stated intention to build “an allied techno-industrial base”. Recent decisions have included elements that clearly discriminate against allies in Europe and South America when it comes to electric vehicles, and there are other examples of the US pouring public money into trying to replace successful European firms.

The EU-US Trade and Technology Council is mentioned numerous times in the NSS. No other part of EU policies or efforts is given the same attention. But it will be important that this really becomes a vehicle for ensuring a level playing field for transatlantic technological and scientific cooperation. If Europe and the US end up with competing and inward-looking industrial strategies, however “modern” they claim them to be, they are both bound to lose. On present trends the risk is not negligible.

On the military aspects of strategy, the interim document was rather restrictive in relation to the use of military power. The NSS is substantially more permissive about the use of force, and the tone when it comes to nuclear issues has shifted.

In the 2017 Obama National Security Strategy there was still talk of “a world without nuclear weapons”, but that vision has since disappeared. Although the new NSS talks about “taking further steps to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our strategy”, there is now a more worried tone concerning what might lie ahead. It notes that there might be an increase in the reliance on nuclear weapons in Russian military planning, as its conventional capabilities are weakened, and there is the deeply worrying prospect that by the 2030s the US “for the first time will need to deter two major nuclear powers, each of which will field modern and diverse global and regional nuclear forces”.

This prospect has major implications. The document states the interest that the US has in strategic stability, and that it seeks “a more expansive, transparent, and verifiable arms control infrastructure to succeed New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)”. Is there any way this could be achieved in the present climate of confrontation? And what would be the consequences if the arms control architecture collapses?

Transnational challenges are prominent in the NSS, but although they are now more daunting than previously, they occupy relatively less space due to the increased weight of the intensifying geopolitical confrontation.

The NSS is clear that “the climate crisis is the existential challenge of our time”, but it does not go into details on how, for example, carbon border adjustment mechanisms of the kind the EU is moving towards can be used or handled.

While the present pandemic is in a declining phase, the strategy rightly notes that “we have a narrow window of opportunity to take steps nationally and internationally to prepare for the next pandemic and to strengthen our biodefense.” Negotiations on a new pandemic arrangement are ongoing among the WHO member-states, and important lessons must be learnt from this pandemic – including by the US – not least on the question of global equity in access to vaccines, tests and treatments.

In parallel, the NSS announces the intention to strengthen the Biological Weapons Convention, which should be seen in the context of “the increasing risks posed by deliberate and accidental biological risks.” This is an emerging issue that has so far received limited attention in Europe.

In spite of the Russian aggression it is obvious that Europe and the EU attract less attention in this NSS than in the previous documents. The NSS states that “with our relationship rooted in shared democratic values, common interests, and historic ties, the transatlantic relationship is a vital platform on which many other elements of our foreign policy are built”, but overall the text on relations with Europe occupies less space than the one on the Western Hemisphere, and the emphasis is very clearly on the Indo-Pacific region. In terms of broader international co-operation on foreign policy issues one should note that issues that normally dominate corresponding EU documents – the importance of the United Nations, international law and multilateralism – receive scant attention in the NSS. This reflects a more traditional US unilateralist approach.

For the US, the rules-based international order is a useful shield for its weaker allies – like the Europeans – but not something that should constrain America itself, which is protected by its own power. The US may come to regret this approach to international institutions if China’s military, economic and political power continues to grow and to rival its own. Most Europeans learned long ago that it is worth accepting constraints on one’s own power in return for constraining one’s rivals.

The Author, Carl Bildt, is co-chair of the European Council of Foreign Relations and a member of the advisory board of the Centre for European Reform. He is a former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Sweden.