Thirty-two years ago, after some 4000 days as Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher was ousted by her own MPs. At the time this seemed exceptional: sacking Tory leaders is now the new normal, with Liz Truss’s premiership breaking a new record by being doomed within her first 40 days.

Exactly ten years ago in a lengthy interview for the Guardian newspaper, MP and veteran cabinet Minister Liam Fox said: ‘The Conservative party needs to learn a lesson from Margaret Thatcher and re-establish itself as a broad church’. I suggest that he learnt exactly the wrong lesson.

The real lesson to be drawn is surely that unless you have a very strong Leader with a coherent mission no single party can realistically straddle diametrically opposed internal factions. Ultimately there is total implosion, and that is where we are today.

The writing was on the wall some 32 years ago, and every Conservative Prime Minster has wrestled unsuccessfully with the same issue ever since.

John Major had additional challenges over ‘Europe’, and the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty in particular. This very underrated Prime Minister finally lost patience with ‘the bastards’, as he labelled them in an off-camera lapse when he thought the microphone was switched off, and even resigned as party leader telling the rebels to put up or shut up. He prevailed over them, but it was a pyrrhic victory. It simply reinforced to the country as a whole the disunity amongst the Conservatives, and they were soon deservedly rejected by the electorate leading to three successive Labour terms.

When David Cameron finally wrenched the Tories back into power he needed the help of Nick Clegg and his Liberal Democrats to form a coalition. But two weak leaders instead of one was no recipe for long-term success, and Cameron became increasingly paralysed by the Brexiteers who had morphed into the European Research Group – an odd name for a group of obsessives who were anti-European and did no research…..

Theresa May tried to build bridges across the internal divide, and showed her best intentions by appointing arch-critic Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary. That didn’t work – for her, for him, for the party or the country – and she was ousted by her own MPs within what was then record time.

Boris had his own solution of dealing with dissent: throw moderate MPs out of the party completely so that those who were left would slavishly support him. That didn’t work: his personal failings would result in a record number of MPs and Ministers all calling for him to go. Time for Truss.

Truss filled her first cabinet exclusively with her own supporters, deciding that there was no need to build bridges with those holding different views if their views could be safely ignored. That didn’t work too well either. Within days the knives were out again, all favouring different candidates as her successor, with each group doing their best to undermine the other. As a last throw of the dice she sacked her Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng for committing the unpardonable sin of totally agreeing with her, while appointing Jeremy Hunt who scrapped key elements of her mini-budget at a stroke.

The question now is not just whether the next leader should be selected again by a small unrepresentative group of paid-up party members or an even smaller group of MPs. The question which has not yet been faced is whether the present Conservative party is capable of being led by anybody. Disunity and division are too deeply baked in. What the country needs now is a rapid general election so the voters at large can decide. Meanwhile strikes, spending cuts and blackouts all await as Truss tries to totter on.

Margaret Thatcher believed in strong leadership where effectively she took all decisions and ground down dissenting views. She famously derided the concept of consensus, saying “to me, consensus seems to be the process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values and policies. So it is something in which no one believes and to which no one objects”.

Because her policy worked for her (until it no longer did) does not mean it is a practical blueprint for the future. Differing opinions should be welcome in any representative Parliament, but such differences are best promoted via different parties speaking out for their own convictions rather than force-fitted into an unhappy single-party straitjacket. That is the lesson for today.

It is a lesson the Conservatives have yet to understand or even recognise. Consensus and compromise are not dirty words but the cornerstones of democracy. The way to achieve them is via Proportional Representation. Labour has said it will always put the needs of the country ahead of the party so they know what they should do when they regain power. Roll on the day….

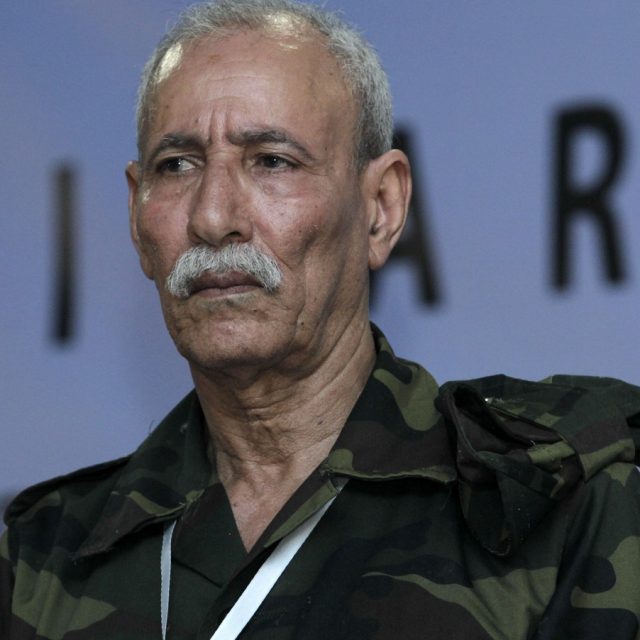

The Author, Philip Bushill-Matthews, is Former Leader of the British Conservatives in the European Parliament.