This article by Guest Contributor David DeBatto, first appeared in the online journal of the IGTDS, the Institute for Global Threats and Democracies Studies, and is reproduced here with their permission.

For weeks now, official Russian government news outlets have been proudly trumpeting the news that Russia has an astronomically low rate of infections and fatalities from the coronavirus in comparison to the rest of the world, especially when compared to America and countries within the European Union (EU). They have such a low rate of infection that Russia has even been able to dispatch doctors and medical supplies to Italy to help that beleaguered EU nation in its desperate fight against the pandemic. Obviously, Russia must have both a superior culture and health care system designed to cope with a crisis like this international pandemic.

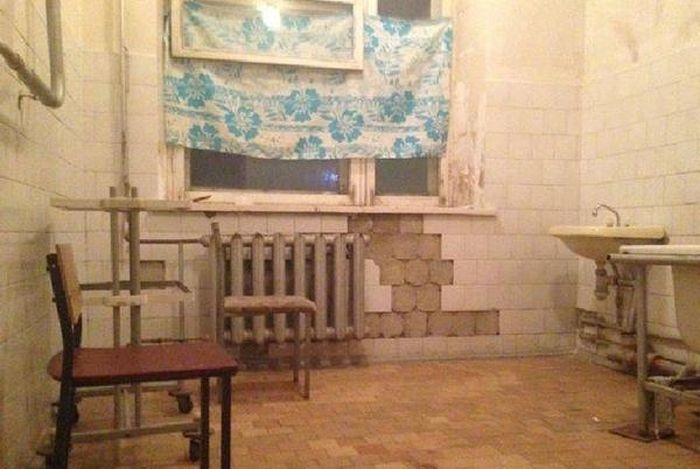

Or maybe not. In reality, the Russian health care system is a disaster. Hospitals are decaying, staff salaries are dismal and modern, functional medical equipment is in desperately short supply. A December 2019 story in Deutsche Welle stated, “According to surveys conducted by various medical unions, Russian doctors actually earn the equivalent of €600 per month (about $648.00), even less than a courier.” I can speak from personal experience that a visit to a Russian hospital can be a jarring and even downright frightening experience.

The only exceptions are the recently built hospitals for the elite upper class in Moscow, and the fees at those private health care centers are way beyond the financial resources of the vast majority of Russians. In fact, if one is unfortunate enough to be an average working class Russian citizen, the only health care option available is the rapidly disintegrating system of public hospitals and clinics scattered across this vast country.

For an example of a visit to an average suburban Russian public hospital, please read the following account from the British newspaper, The Independent, of a 26 year-old Icelandic woman seeking treatment for chest pains. A word of caution: this is not for the faint of heart.“The floor was soaking wet and muddy, and the toilet was jammed full of urine and feces,” she wrote in a blog post, since deleted, about what she called her “nightmare” in Penza. Holding her sweater over her nose to keep out the stench, Rún tried not to touch anything in the restroom: “The sink was full of blood,” she wrote.

After doctors suggested carrying out an operation to “make sure” her internal organs were “working properly,” Rún decided to leave. It later turned out she had been suffering from heartburn. And this is not an isolated or uncommon experience. A Russian woman I have known for many years (let’s call her Svetlana), confirmed many of the details of the story in the preceding paragraph based on her own experiences in the Russian public healthcare system. “Most public clinics are from Soviet Union times. They are very old and need renovation. Paint is peeling, ceilings often have holes and water marks where the rain pours in, lights are broken, patients sit or lie on the floor in hallways, and bathrooms are disgusting. If they have modern medical equipment, which is rare, no one knows how to use it so it sits unused.

Doctors and nurses are rude and tell you only basic facts about your medical condition and get angry if you ask questions. You cannot even see your own medical file. You must wait for weeks or months for an appointment.” “Except for expensive private dentists, dental patients in public clinics do not receive anesthesia for any dental procedure, regardless of how complicated or painful.” This last part I found difficult to believe, but when I asked other Russian friends about this, they confirmed Svetlana’s account about the absence of dental anesthesia and her description of conditions inside the aging public hospitals as well.

Svetlana and the other Russians I spoke with for this interview also agreed on another fact: no average Russian goes to a doctor, hospital, or dentist unless they have either unbearable pain or are seriously ill to the point of almost dying. Otherwise, they deal with it themselves within their family.

So, if the average Russian rarely, if ever, goes to a doctor or clinic, especially for something as relatively minor as a low-grade fever, sore throat or runny nose (classic viral symptoms), how are they being tested for the coronavirus? Chances are they aren’t.

Even if someone wanted to get tested for the coronavirus or anything else, there aren’t nearly enough healthcare facilities to serve them. According to a report by the Russian State Statistical Service published by Borgen Magazine in 2018 on the declining public healthcare system, “In rural areas, 17,500 towns and villages have no medical infrastructure whatsoever. According to the State Statistics Service, the number of health facilities in rural areas fell 75 percent between 2005 and 2013. This number includes a 95 percent drop in the number of district hospitals, and a 65 percent drop in the number of local health clinics.”

Although this number has improved somewhat recently, the number of doctors leaving the medical profession over low wages has actually increased, leaving Russians with even less options for treatment. This brings us to the question of the dramatically low numbers of Russian people who have been infected by the COVID-19 virus.

As of late on April 1, 2020, the official Russian government numbers stood at 2,237 confirmed cases of the disease and 23 deaths. That same day President Vladimir Putin was quoted as saying, “the situation in our country looks a lot better” than Europe and was “under control.” However, just prior to Putin’s statement, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin stated the obvious fact that Putin could apparently not bring himself to admit publicly. “The testing volume is very low, and nobody knows the real picture.” Thank you Mayor Sobyanin for cutting through all the propaganda and happy talk and telling the truth. The fact is that no one, especially the Russian government, knows the true extent of COVID-19 infections or deaths within Russia because the overwhelming majority of Russian citizens rarely, if ever, visit a doctor.

Therefore, the overwhelming majority of Russian citizens have not been tested for the coronavirus. It is that simple. Also, Russians do not exactly believe in obeying rules, especially when they might pose an inconvenience to their lifestyle, so social distancing and other suggested safety measures are probably being ignored by a large percentage of the population. With the dormant phase of COVID-19 now known to be up to 2-3 weeks, and with millions of Russians returning home from work, school and vacations abroad, it is only a matter of time before the number of Russian citizens infected with COVID-19 increases exponentially. Unfortunately for Russia and the rest of the world, because of the culture within Russia of both noncompliance to rules and their avoidance of doctors, it may be a very long time, if ever, before we learn the true extent of the unfolding healthcare crisis in Russia caused by COVID-19.

Certainly, it is not in the best interest of Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin to tell us the truth anytime soon. By that time, Russia and the rest of the world may be a very different place.

The Author, David DeBatto, is a retired U.S. Army Counterintelligence Special Agent. He served in Iraq as a team leader of a tactical Human Intelligence Team (THT). Prior to his deployment to Iraq, David was an instructor at the reserve U.S. Army Counterintelligence Special Agent course. He has published four novels for Grand Central Publishing and is currently finishing a memoir of his experience in Iraq. David has also written articles for Vanity Fair, Salon.com, The American Prospect and The Washington Monthly.