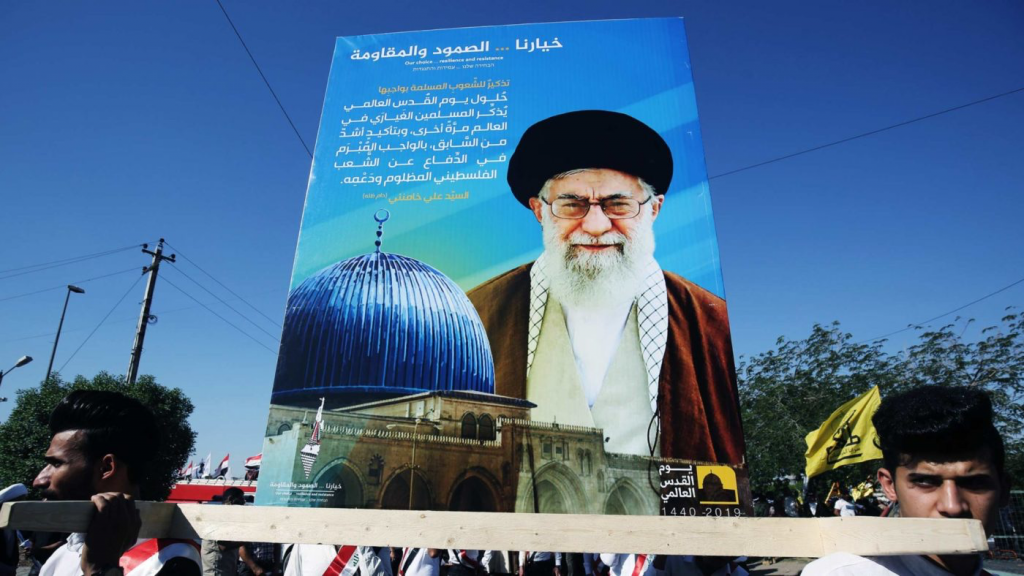

Tensions between Iran and the US, which can ignite the entire region, are rising with the alleged sabotage of oil tankers, the US drone shot down by the Revolutionary Guards and heated rhetoric on both sides, writes Majid Golpour. This has fuelled the US to impose new sanctions directly on the Supreme Leader, Mr Khamenei, and his holdings. In addition, Iran’s last ultimatum to enrich uranium at a higher level would be a violation of the terms of the nuclear non-proliferation pact.

This could lead one to wonder if Europe’s strategic approach with Iran through the nuclear agreement (JCPOA) is working? Whether or not we like President Trump, agree with his politics or his ‘Tweet diplomacy,’ one thing is clear: his administration has a view on who is really in charge in Iran, and how and where the money is moving.

Europe, however, seems blind or unconcerned about the power and influence of the holding companies of the Supreme Guide, which pervert the decision-making processes in Iran. EU diplomacy seems to be overwhelmed, or to ignore both possible solutions to the current crisis, namely important compromises or war.

The unelected financial oligarchs and ‘security networks’ are the real decision-makers for Iran’s nuclear project and its regional expansion. Decisions are taken, not by President Rohani or Mr Zarif, but by the close circle of the Supreme Guide, which has alone profited from the financial openings afforded by the JCPOA.

The EU’s strategy seems to sacrifice long-term US relations in favour of short-term business openings with Iran’s clerical oligarchy. Analysis of the factors that have hindered the JCPOA’s implementation show that the roadblocks are not generated by President Trump alone, but are mostly related to the internal workings of the Iranian political system and its structural dysfunction.

As soon as the JCPOA was signed, political jockeying between the three main factions (ultra-fundamentalist, conservative and moderate) plunged Iran into internal crisis on its own issues: constitutional legitimacy, the economic model and geopolitical positioning. This volatile domestic situation will continue to increase the risks for European businesses.

To anticipate crisis and avoid the agreement’s breakdown, such risk factors at the heart of the Iranian political system should have been identified and precautions taken to mitigate the situation. Unfortunately, such regulatory mechanisms were not implemented from the beginning of the agreement, and in the case of a new JCPOA, this should be the priority.

It is essential to understand the mechanisms of power and financial distribution between the factions and the ‘unelected institutions’. European companies must perform audits of Iranian suppliers and partners to understand the ‘how and who,’ to ensure their activities do not fall under US sanctions and thus protect their investments. This includes deep investigation and legalisation, with equal importance on the entry and exit of capital, and the physical and legal holders of partnership units.

Europe must also understand who they should negotiate with, work for a non-aggression pact on Iranian ballistic missile testing, and agree on a pact of good business conduct, with a white list of legitimate businesses for access to the European market. Such measures would help fill the gaps in the initial agreement.

For Iran to merit its seat at the world trade table, it should adhere to at least some rules and standards and deliver visible benefits for its people. Documented figures indicate that billions of dollars of ‘black capital’ have already ‘officially’ escaped from Europe’s financial and banking system.

In the Iranian scenario, human rights are directly linked to free and transparent business. As such, the legitimate expectations of the Iranian people for economic improvement have been denied to the benefit of these holding companies which continue to monopolise access to the Iranian market.

It is thus essential that Europe deepen its sectoral knowledge of the Iranian market for which the US, Russia and China have a considerable lead. Until the long-term high-level risks are reduced, European companies will not choose the minor short-term ‘advantages and facilities’ of INSTEX.

Once on the ground, they will quickly understand that access to credit, liquidity markets, foreign exchange, property, stock and major import-export markets … all fall directly or indirectly under the monopoly of the Supreme Guide’s eco-financial empire, now under draconian US sanctions. And if the INSTEX payment channel provides the Iranians with a channel to possibly move more ‘black capital,’ this will do nothing to improve transatlantic relations or Iranian lives.

With the recent elections, there is an opportunity for the EU to rethink its strategic diplomacy on Iran and the JCPOA. This could offer Europe a new leadership position, particularly in the area of financial fraud, by strengthening links with Iran’s private sector and civil society.

In this strategic perspective, if the current JCPOA dies, we could still say ‘Long live the JCPOA.’

The Author, Dr. Majid Golpour is a Senior Business Analyst with PTK and an Associate Research fellow at ULB.