Has indoor air quality worsened during the pandemic and what factors such as potential health risks from mineral wool insulation can be addressed?

The recent Clean Air Day had the aim of increasing awareness and understanding of air pollution, its effects on both climate change and public health and what needs to be done to reduce it. As outlined in Envirotech Online, the World Health Organisation and European governments Government recognise that air pollution is a major public health risk and poses the single greatest environmental risk to human health. Of course, clean air does not refer only to the outdoor environment, but also to our indoor habitat, where most of us have spent significantly more time during the pandemic. How has our indoor air quality fared as the pandemic progressed? What factors can we consider to improve our health and safety at home? What should we make of continued concerns that materials used in our home, such as mineral wool insulation, could potentially cause a risk to respiratory or skin health?

COVID-19 lockdowns have led to reduced travel and emissions, and therefore, improved outdoor air quality. According to IQAir’s 2020 World Air Quality Report, some 84% of nations reported improved air quality compared to 2019. But what has the pandemic meant for indoor air quality? Last year, Airthings, a global authority in indoor air quality and producer of indoor air quality solutions reported a sharp increase in indoor CO2 and airborne chemicals (Volatile Organic Compounds or VOCs) due to the lockdowns. As many people now work as well as live in their homes, houses and apartments have taken on the dual functionality of being both personal living spaces, office and school spaces. As Environtech Online explains, good indoor air quality is not only central to our health, but our productivity as well. A year later, Airthings has completed more analysis to learn if poor indoor air quality persisted into the rest of 2020.

The Airthings study found that there were higher levels of CO2 and airborne chemicals (VOCs) in both Europe and the United States after the lockdowns, compared to before. Overall, Europe had higher levels on average than the United States. As reported in Environtech Online, Airthings’ analysts looked into CO2 trends during typical work hours to understand how working from home has affected indoor air quality in major markets. In both Europe and the United States, there is a noticeable spike in March when the lockdowns began and another steady rise in autumn when many countries went into a second lockdown. Europe’s CO2 levels were significantly higher throughout the entire year, and we see a 16% increase in CO2 levels from late February, just before the lockdowns started, to the end of the year. In the United States, just before the lockdown started, there was more than an 11% increase.

Breaking Europe down into individual markets, the expected peak in CO2 in March was observed for Norway, Germany, and the UK. In the UK, an even larger peak is apparent when CO2 levels rose over 25% when the second national lockdown went into place at the beginning of November.

As outlined by Environtech Online, CO2 is a greenhouse gas that is natural and harmless in small quantities. Most commonly produced indoors by the air we exhale, CO2 levels build up indoors with more people, more time, and less ventilation in a room. It’s important to monitor indoor air quality as high concentrations of CO2 can cause restlessness, drowsiness, headaches, and more.

With the home environment now doubling as the work and school environments, healthy CO2 levels become important to job performance as high concentrations are directly correlated to low productivity and decreased cognitive abilities. In fact, studies show that as CO2 levels rise, people have a much harder time learning, performing simple and complex tasks, and making decisions. Good air quality improves productivity and can result in a 101% improvement in decision making. Fresh air will also aid in a better night’s sleep and in avoiding the “stale” air feeling which comes from increased levels of CO2. A good night’s sleep will help in increased productivity and focus the next day.

To decrease CO2 levels, improve the airflow throughout a home by opening windows or vents for 5 – 10 minutes, several times a day. Additionally, it is important to regularly replace air filters in indoor fan systems.

The Airthings study found that VOC levels in the UK, Europe and the United States over lockdowns were higher than the recommended level for nearly the entire year; at its peak of 390ppb, airborne chemicals (VOCs) were 50% higher. Low levels of airborne chemicals (VOCs) are considered to be under the threshold of 250ppb. In Germany, several spikes were observed in airborne chemicals throughout the year. By the end of the year, the average level of airborne chemicals (VOCs) had increased nearly 7% since March. The UK follows a similar trend to Germany, with several peaks, whereas levels in Norway are more stable after the initial peak in March.

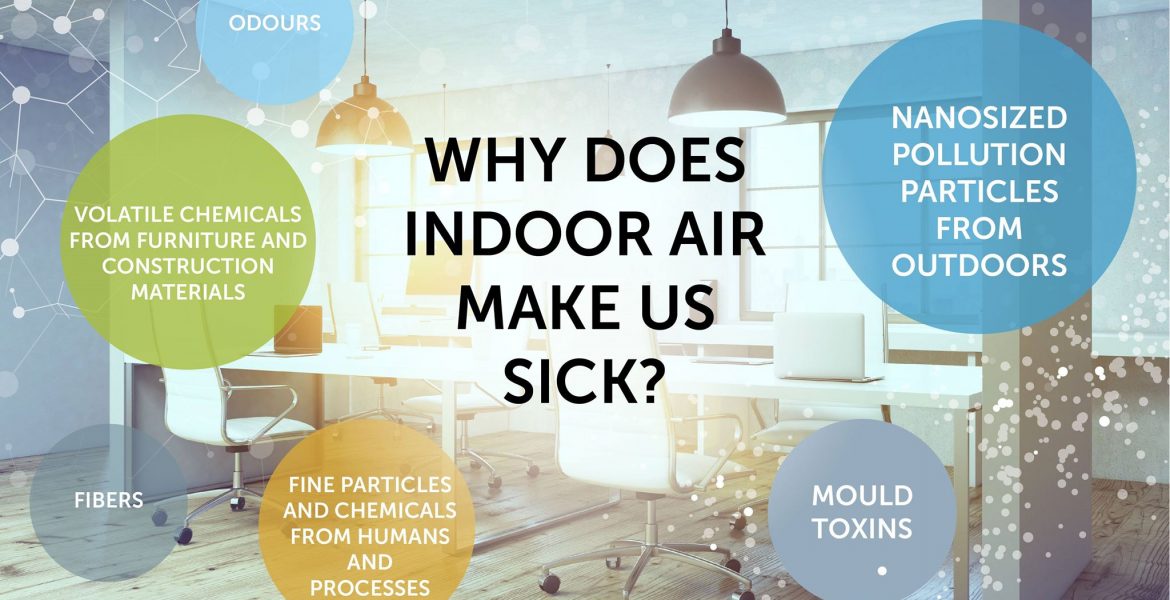

Airborne chemicals (VOCs) are a combination of gases and odours emitted from many different toxins and chemicals from everyday products and activities such as cooking and cleaning fumes, new furniture, paint and craft products, and more. In the short term, airborne chemicals (VOCs) can cause headaches and minor eye, nose, and throat irritations which can impede optimal performance when working from home. However, there are more serious long-term health effects such as liver and kidney damage.

The recent focus on the importance of indoor air quality, especially in our homes since many of us now work and live in them, has also brought increased concern over some of the materials we have in our homes. One example is concern over potential health risks associated with the insulation material Manmade Vitreous Fibres, also known as mineral wool. Those health concerns are best explained by Dr. Marjolein Drent, a lung disease expert Maastricht University, in the Netherlands: “The effects of the fibres of glass wool and stone wool can be compared to those of asbestos. In the past we did not know asbestos was very dangerous. The results of the effects of fibres in glass wool and mineral wool are only being seen right now, so we must deal with it carefully. The point is that these substances are harmful, but people do not realise it sufficiently, and that is something we have to worry about. It is too easily accepted that ‘we have a replacement for asbestos’. But the replacement may not be as good as we thought it was at the beginning, there is insufficient attention given to this fact.”

Questions have been raised as to why mineral wool is still being widely used. The answer to this question lies in the method used for testing mineral wool. Mineral wool was originally classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Agency on the Research on Cancer (IARC) as carcinogenic and hazardous to humans. The mineral wool industry then altered the composition of their product, which then underwent further tests. In 2002 mineral wool was declassified as a carcinogen. However, it has now emerged that the product as tested was different from that which is commercially available, in that an important ‘binder’ had been removed.

Environtech Online’s article concludes by reminding us that education on the importance of good indoor air quality is critical, allowing insight into air quality contaminants and the knowledge to take action with simple steps like opening a window or turning on a fan. We also must take a “whole home” approach and be mindful of the materials we install and remove from our home.