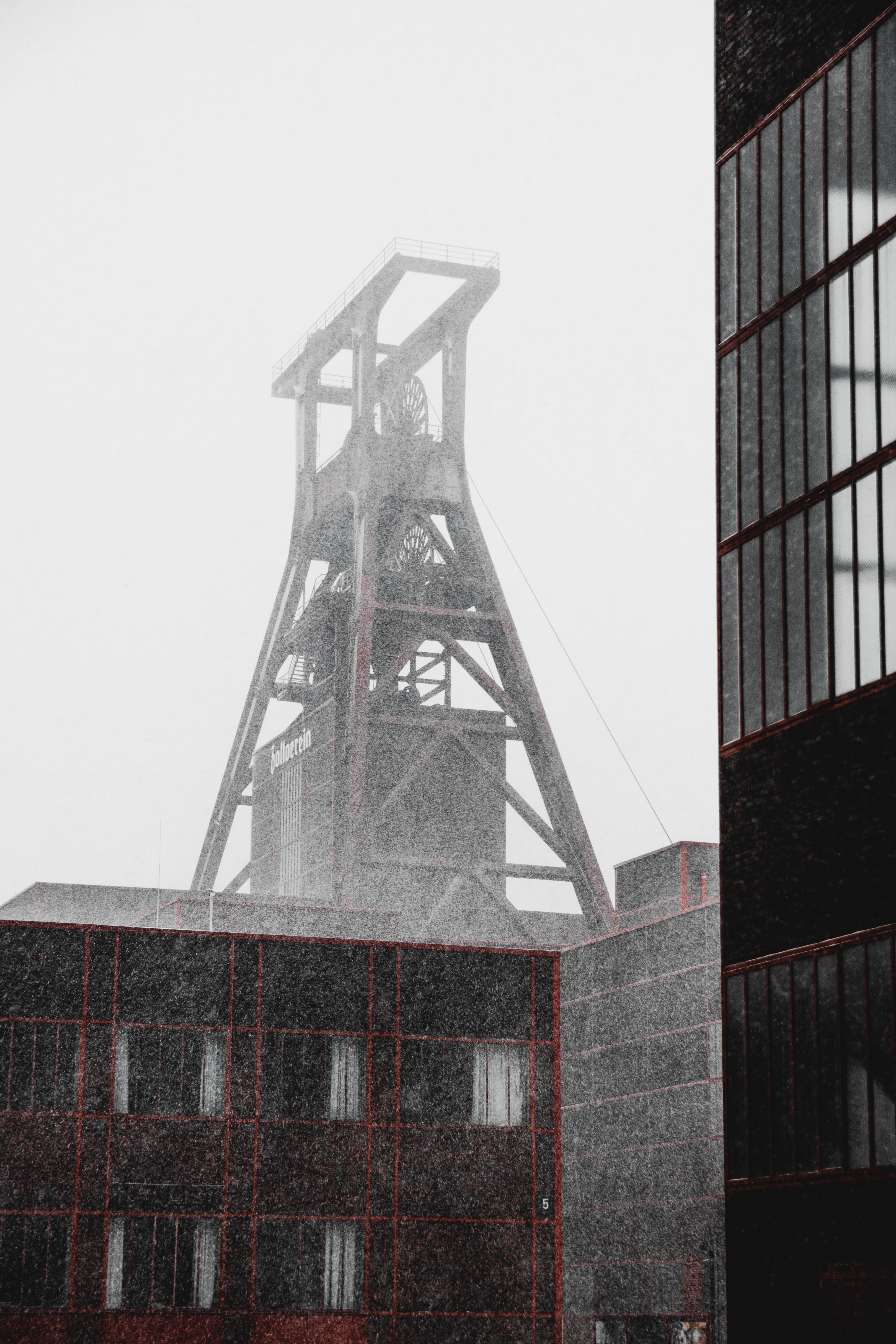

Photo by Kai Pilger on Unsplash

Special commemorations will take place in Charleroi next month in memory of one of the worst ever disasters in Belgium.

On 8 August 1956 some 262 miners perished in the Bois du Cazier in Marcinelle.

They included 136 Italians, more than half the victims.

Today, the site is preserved as an industrial heritage site and a museum now stands on the site of the old mine.

The commemorations on 8 August will start at 8 am, almost the same time as the fire started destroying the mine that killed so many. In the main square of the old mine a bell donated by Italian bell makers was installed.

It will chime 262 times, once for each victim. A lone voice will then call out the names of the victims, one after another.

Former miners and relatives of victims’ families are expected to attend the commemoration. The victims came from 14 different countries but the majority were Italians. Antonio Tajani, a former Italian MEP and president of the EU Parliament and now the Italian foreign minister, may also attend.

Very few of miners who worked at the pit are still alive.

The Bois du Cazier was a coal mine in what was then the town of Marcinelle, near Charleroi.

At 8.10 am disaster struck when a lifting mechanism was triggered before the coal car had been fully loaded into the cage. Two high voltage electric cables were broken, starting a fire. The fire was aggravated by the oil and air lines damaged by the mobile cage. Carbon monoxide and smoke spread along the galleries. A few minutes later, seven workers managed to reach the surface, enveloped in thick black smoke. Despite many brave rescue attempts, only six other miners were saved from the mine.

The disaster triggered unprecedented emotion and solidarity in Belgium and abroad. The press, radio and television reported the 15 days of anguish that followed, the rescue operations with the help of the Gare Centrale de Secours Houillères du Nord-Pas-de-Calais and the Essen Rescue Center of the Ruhr.

Families, women, mothers and children clung desperately to the mine gates and a meagre hope. The remains of the bulk of the still missing miners were found behind an air tight door where they had tried to escape the fire.

Veteran Italian journalist Maria Laura Franciosi has researched the tragedy and was instrumental in setting up a museum on the site.

She told this website: “I am glad I was able to meet a miner in Brussels in 1995 who told me “I was bought for a bag of coal”.

This is the title of a 400 page book, in Italian and French, she wrote on the tragedy, called “Per un sacco di carbone”, in 1996. It contains the stories of 150 miners.

At the time she was working for ANSA, the Italian News Agency as a deputy chief of office and had some contacts with local journalists who helped her campaign to preserve the site of the devastated mine.

She recalls, “Despite this being where so many people died the mine was about to become a shopping centre. This is what Charleroi was planning to do.”

She adds, “It took several weeks for the safety teams, miners who knew every area of the mine, to find the bodies of the miners. Those who did not die in the fire were killed by the lack of oxygen or drowned in water that the fire brigade had been throwing into the mine. It was a massive tragedy.”

She added, “When Charleroi decided that the site of the mine should be rejuvenated by transforming it into a shopping centre I was called by miners in the area and they asked me to try to help them save the memory of their friends.”

It was the president of the Associazione Minatori Marcinelle, Silvio Di Luzio – a miner from Abruzzo who had been engaged in the safety operations in the mine for the whole period of the search for

survivors – who was instrumental to help her campaign.

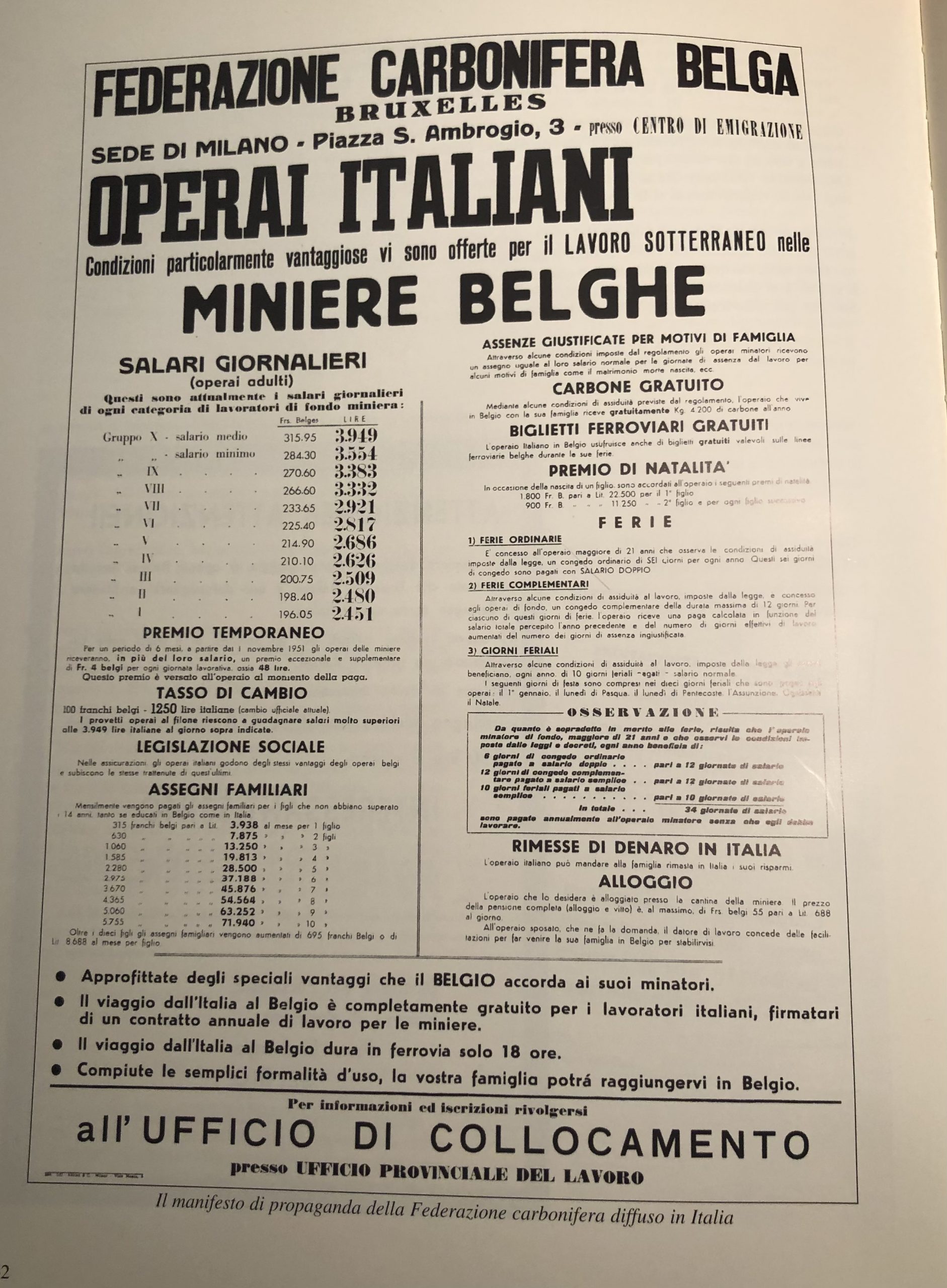

She said, “The reality was that thousands of people were sent to work in those Belgian mines even if they had no training for that job”.

Many died and many started to cough the coal accumulating in their lungs. There were 1,000 workers leaving Milan by train every week. When they arrived in Belgium were chosen by the mines managers at the train station and sent to the “cantines” where they shared bunk beds with other miners and sent to work in mines the following day.”